In January I, Sebastian, got the chance to join Klaus on his annual post-harvest trip to Kenya. The main aim of this trip is to select the precise coffees we will buy from this harvest (more about this later) and beyond that to exchange with the farmers with regards to the out-turn of the harvest, their experiences and our views and ideas of relevance.

I will share my journal entries here, hoping that this format will give you a good insight in the structure of this trip.

Day 1 – Nairobi

We are getting off to an early start from our hotel in Nairobi, as we have a pretty packed day ahead of us. The first, early highlight of the day: drinking Kenyan coffee in Kenya at the breakfast buffet. Not the tastiest cup of Kenyan coffee ever but still accompanied by a special feeling of importance on my side. Klaus knows the drill and is more into the crepe station.

After breakfast we head straight to the marketing agent that Kieni has chosen to be represented by this year: Tropical. The system in Kenya is set up in a way that every coffee cooperative has to work with a marketing agent, which provide abroad range of services to the farmers, from dry-milling and exporting the coffees to providing training and consultation to the farmers. Most importers and/or roasteries (the ones that source their coffees directly- like us) buy their coffees every year from the same marketing agent, selecting coffees from their portfolio and having their contracts with them. The Coffee Collective is in a slightly different position, emphasizing the importance of the straight relationship to the producer level, in this case the Kieni factory. Most importantly this results in The Coffee Collective being the maybe only coffee company having established a 3-party contract, which allows us to deal directly with Kieni, as opposed to doing this via the marketing agent.

Arriving at Tropical I am stunned by the dimensions of the operation. Tropical moves around ⅓ of the annual Kenyan coffee production and this time of the year the coffee bags in their warehouse nearly reach the (pretty high) ceiling. Our company guide is proud to point out that this is the only “coffee warehouse” in whole of Kenya, everything else is a “warehouse with coffee in it”. Everything was built and designed with optimal storage conditions in mind, from air circulation systems to insulated walls.

In their cupping lab we set out with tasting all the different out-turns from Kieni. The out-turns refer to individual batches of the harvest, separated by the date they were processed at the factory. The Coffee Collective always gets first pick on coffees from Kieni, a tribute to the long and trusting relationship that has been built up over the last 8 years.

After Kieni we set out to taste more than 60 other coffees from different factories, mainly from the Nyeri region. Nyeri is one of the most important coffee producing areas in the country and is widely respected for producing some of the highest quality Kenyan coffees. Some attribute this partially to its geographical disposition, it being a valley nestled in between the slopes of Mount Kenya and the Aberdares, thereby having a relatively large amount of highly elevated areas.

The tasting of more than 200 cups allows us to get a really good overlook of this year’s harvest, so to say a snapshot of some of the best coffees produced this year all over the country. This tasting also defines to some degree our next couple of days, as its really luring to visit the factories that are behind some of the cups that really stood out for us.

After the last round of cupping I definitely have reached my point of taste- saturation and we leave in deep respect of the staff continuing to slurp away in the cupping lab, grading up to 2000 coffees this week alone. Our heads buzzing with all the caffeine we make our way to our hotel, close to the office of Tropical in Ruiru.

Day 2- Ruiru

We raise with the sun and after breakfast start our drive north to Kirinyaga county, heading straight towards the Mt. Kenya National park. The landscape around us begins to change gradually, as we leave the rather dry, desertous area around Nairobi and enter really lush and green farmland areas. We spot a lot of maze, it being the main stable in the Kenyan kitchen. To my delight I discover that this year’s mango season in full swing, with farmers selling their produce in by the kilo in roadside stalls.

Even though we find ourselves in the middle of dry season now it’s still very green, with the scenery bursting with beautiful vegetation. The farming here is mostly taking place on a small, subsistence scale, vastly different to many common farming areas in Europe. We spot a lot of small operations, nestled in between mountain slopes and forests, horticulture with all kinds of fruit trees and vegetables planted in the maze fields. After a few hours of driving we are now entering the country’s coffee producing area, with coffee estates starting to slide by the view from the car seat. Besides coffee we see also Nepir grass cultivation popping up, which plays an important role in the coffee production. Farmers feed the grass to their cows, which produces a very phosphorus manure that is being applied to the generally phosphorus deprived soil.

We are now leaving the paved main road onto a little dirt road leading to Konyu factory, which is part of the Kabare co/op. The processing here is mostly done, and we just spot a few last p-lights on the drying tables. The scenery which this factory is nestled into is breathtaking- its located on a steep slope with the background vista being filled out by waterfalls and tea plantations. The factory managers explains that many local farmers believe that a close proximity of coffee and tea has a positive effect on coffee quality- a statement that doesn’t really have any scientific backing but then- who knows? Fact is, however, that the coffees that stood out to us most on the cupping table yesterday didn’t have any tea plantations nearby.

Before taking off we get to sign the visitors book, which is a common practice among all factories. It’s always fun and sometimes borderline awe-inspiring to consider who, and at which point in history, held this book in their hands. in this case we find entries from Peter and Klaus from more than 8 years ago- a beautiful testament of continuity to what we do on an everyday base.

After the factory visit we head further north to Nyeri county- an amazingly fertile and lush landscape full of forests, maze, mangoes, bananas and coffee.

The first factory we get to visit here is the Kiangoi factory, where we receive a warm welcome by Joseph, the chairman, and Emma, the manager. Its a medium-sized factory with a total of 378 active members. Upon inquiring on how the harvest went we meet a piece of information that resonates pretty much throughout all our visits here in the future: really low harvests.

The factory usually produce around 400,000 kg of coffee, this year it only ended up at 180,000 kg. Joseph and Emma explain to us that they were able to pay out 83.95 Kenyan Shilling to farmers per kilo, which was very happily received. The factory, and really all factories here in Kenya, provide a really important service to farmers, not only processing their coffee and transporting it to the dry mill but also providing farming inputs to farmers at an advance- e.g. lime which is being used against the high acidity in the soil. The soil in this area has a high nitrogen content, which causes it’s PH value to go into the acidic range. Farmers observe which weed is predominant in their farms and based on that determine when and how much lime and manure to apply.

In the evening at our hotel in Karatina, where we are being visited by Josphat, the mill manager, and Charles, the chairman, of Kieni. Klaus brews some Kieni from their last harvest, while I lean back and take in the magical moment- drinking and talking coffee with some of the people behind it, right at the place where it’s been grown.

Day 3- Touring Nyeri

Completely unexpectedly we find and espresso machine in the restaurant of our hotel. Even more unexpected the barista of the hotel turns out to be really excited about coffee and, once upon being informed about Klaus’ World Championship laurels, is very eager on being shown a few tricks, in particular latte art (for the “gram” you know ;-)).

After a little milk steaming- and pouring training we set off to what will be a long day of visiting different factories in Nyeri, starting off with Kangocho, part of Gikanda society. They have 800 active members and ended up harvesting 660,000 kg of cherries, which is significantly less than in other years (normally around 1.25 tons). Also here the farmers faced problems with the drought, whose effects we end up seeing all over the area. Here we see a lot of the old wood drying tables having been replaced with metal ones, which can be quite an investment for the factory but it really pays off in the long run as they last much longer.

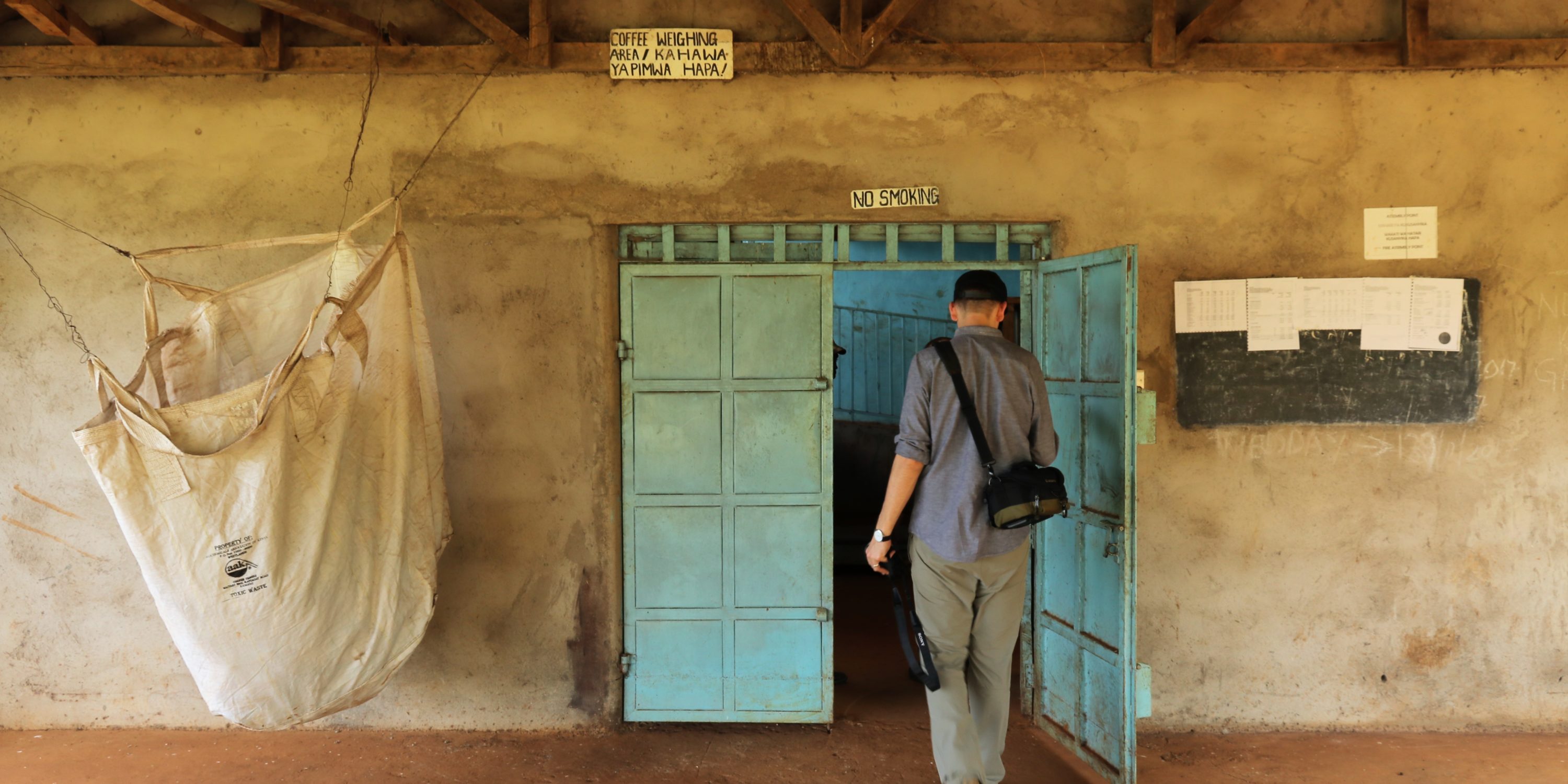

The mill managers gives us a good tour of the place, proud to show us the new digital scales and laptops and the 2 newly renovated hoppers next to collecting area- one for perfectly ripe ones, one for under ripe.

From the point on that the coffee cherries have been accepted from the farmer they are now always being handled separate, from the hopper into separate fermentation tanks, where they ferment for around 14h, depending on the temperature (lower temperatures- longer fermentation). Before they go into the fermentation tanks they will be depulped though, in the process of which the beans will be separated into P1, P2, sometimes P3 and P light. P1 is generally regarded as the highest quality level- having highest density. Around 60 percent of the total harvest here are P1, 30 percent P2 and 10 percent P light. From fermentation tanks the beans go into intermediate tanks, where they are being washed first. The second washing and another round of separation takes place in the washing channel, where lighter/ lower quality beans float up. After the final washing the beans go either straight onto the skin drying tables or, if there is currently no space, into soaking tanks, where they are being kept in clean water, which is being changed every hour, until they can be moved onward.

On the skin drying tables most of the water will be removed off the seeds, which will afterwards spend 7 days on final drying tables. The mill-manager will remove them from there when moisture content will have dropped down to around 15-16%. Once that point has been reached the coffee will go into conditioning bins for about 3- 4 weeks. Afterwards back to the drying tables for final drying and sorting- at this point the moisture content should be at about 10-12 %. The next step will be the bagging and transportation to the dry-mill.

The pulp which has been removed from the seeds in the de-pulper gets collected and picked up by farmers, who then apply it later to the fields. At the moment of our visit the de-pulper taken apart, with the metal disks being brought to Nairobi for servicing.

We also see some Mbunis on the drying tables, which is the lowest quality out-turn of the harvest. They are being processes as naturals and are being kept separate from the other coffees not only in the processing but also in the bookkeeping and billing, as not to distort the prices.

After Kangocho we are off to Ndaro-ini, which is also part of Gikanda society. Their harvest went from 800,000 kg to 460,000 kg, which is the second low harvest in a row. The factory just got a new chairman, which, like in the other factories, is being re-elected every 3 years. There is a few criteria which have to be met to be eligible for the vote, most importantly the candidate has to be a good farmer him/herself. The newly votes chairman informs us that in the peak season the factory processes around 40,000 kg of cherries everyday. With all that coffee around after the harvest it’s a very common sight to see a big watchtower on the premises of the factories, to protect the operations against theft.

Last factory to visit that day is Tegu, a factory from which we have purchased coffee before and which was tasting fantastic on our first round of cupping on Monday. Tegu is part of Tekangu society and produced 265,000 kg of cherries this year. Also here that’s much less than usual but everyone is expecting a re-bounce in the harvest this coming year.

Day 4- Kieni

We are starting off with a visit to Kieni, from which we have been buying coffee for the last 8 years. For me it’s amazing to see the connection between Charles, the chairman, Josphat, the manager, and Klaus.

Kieni processed 552,000 kg of cherries this year, which is a bit of an increase from the 480,000 kg the year before. We brought a moisture meter as a present- the money having been collected in the course of a birthday-celebration day in February, where our wonderful customers provided at total of DKK 27.678 (ex Danish VAT/Moms). Besides the moisture meter Kieni have used the money to construct 8 new metal drying tables, which are much easier to maintain than their wooden counterparts.

From customers, via The Coffee Collective to the producers- a beautiful demonstration of how this is a mutual partnership, where quality, respect and fairness are being pursued as an interlinked whole.

We are meeting the farmers as partners, learning from them and whenever possible giving our inputs for the goal of continuously improving quality, which will allow for them to get higher prices for their cherries. The moisture meter will allow them to perfectly time the removal of the beans from the drying tables. The moisture content ideally should be between 10-11 %, otherwise there will be an effect on the taste.

Until now the factory manager determines the moisture content by biting the green coffee- the higher the water content the easier the teeth cut through. Once can get very skilled in getting a precise idea about the moisture content this way but with the moisture meter Kieni will have another tool allowing them to get consistent data. With this tool now in place we are planning to start a process where the mill manager will document the moisture content at the factory, just before shipping. Then we will get another reading from the dry mill and will finally do our own reading once the coffee is here in Copenhagen.

This will allow us to get a better insight into what is happening to the coffee in transport and throughout the whole supply chain and ultimately to determine what the moisture content should be at the factory level before shipping out.

Later we are meeting with the manager and chairman of Kieni to tell them about our impressions of the different outturns and what we will pay. In the latest auction in Nairobi the highest price for AAs was around 485 dollars per pound- we offered 550 to Kieni, which is higher than the highest bid on the auction. For me it’s really amazing to consider our role here as price pushers, not necessarily confusing a good price with a fair price.

The farmers consider the 485 dollars at the auction a good price but we believe that it can only be seen as good within the context of a skewed market and that a good price in the current system does not necessarily equal what we consider a fair price. We really hope, that our collective effort- stretching from farmer via roaster to barista and finally to the consumer- will contribute towards a different way of looking at the ways of how our consumption patterns can make a significant difference to fellow humans in other parts of the world. Only if we meet each other in a transparent, honest and respectful way can we work towards a world less skewed by drastic inequalities and profits being the ultimate compass of how to conduct business.

Our offer was really well received and right after we took off to visit the Shamba of a Kieni farmer, who is currently busy with pruning the coffee trees. It’s beautiful shamba, sporting no monocultural rows but rather horticultural practice with coffee trees growing wildly in between avocado, banana, mango and other trees. There is also a cow for manure, which will be used as a fertilizer.

Straight from the shamba we head to meet the whole Mugaga board, consisting of the chairmen of all the individual factories plus a board-chairman. We brewed some coffee, Kieni of course, for the otherwise rather tee-affine board and had a really good exchange about the current situation of all the other factories besides Kieni and our much appreciated role with regards to pushing for higher returns for farmers. It’s really special to see the people behind some of the worlds best coffee sitting together in such a humble way and mostly being concerned about how to get better prices for their farmers.

Day 5- Back at the cupping table

We are off to an early start and make our way down to Karatina- leaving the lush Nyeri valley behind. We are heading to the headquarters of Tropical to cup and finalize our purchase decisions.

We are starting off with the different out-turns from Kieni- selecting a total of 4 AA lots and 1 AB. We always try to have a Kenyan coffee besides Kieni in our portfolio, preferably something with quite a different taste profile which allows for us to showcase the broad spectrum of flavours that can be found in coffees from such a small area as Nyeri. For us it was clearly an amazing coffee from Tegu, which we visited earlier, that really stood out and of which we purchased 1 AA lot. It’s been really exciting seeing this coffee being brewed and enjoyed in the shops since it’s launch 2 weeks ago, and hearing all the hard work involved in producing this exceptional coffee resonating in guests’ feedback.

New perspectives

For me this trip produced an absolutely profound deepening and broadening of perspectives, and I am infinitely grateful for everyone part of The Coffee Collective that allowed me to embark on that journey. Among a broad range of significant impressions there is two things which left a deep impact.

First, a sense of shrinking of distances. Standing with farmers in their horticultural fields in the Nyeri valley, seeing their coffee drying on the tables at the factories and meeting its producers in person absolutely changed my perception of coffee as an exotic product. It just takes some 8 hours on a plane and you will meet the people and their world behind that cup of Kieni or Tegu, all of us engaged in a shared commitment to improving quality and enabling farmers’ life a life we would like to live ourselves.

Secondly, fully grasping The Coffee Collective’s role in the coffee market- pushing for fair, not just good prices and being driven by a deep commitment towards quality and fairness, towards everyone involved in the journey from seed to cup.

Would you like to get our different coffees delivered directly to your doorstep? We've got you covered.

Address

Coffee Collective

Godthåbsvej 34B

2000 Frederiksberg

CVR: 30706595

Contact

mail@coffeecollective.dk

+45 60 15 15 25 (09.00-15.00)

Coffee and cookies

This site uses cookies.

Find out more on how we use cookies.